Do We Actually Need That Many Data Centers?

The AEC industry depends more than ever on digital infrastructure, and data centers form the physical backbone of that ecosystem. They are multiplying rapidly to support the rising demand from AI, cloud services and digital design platforms.

But what exactly are Data Centers, and why is everyone talking about them?

Data centers are massive physical facilities that house thousands of servers responsible for processing, storing, and distributing digital information around the world.

They are where the cloud becomes tangible, powering everything from BIM models and simulations to AI systems and real-time collaboration tools.

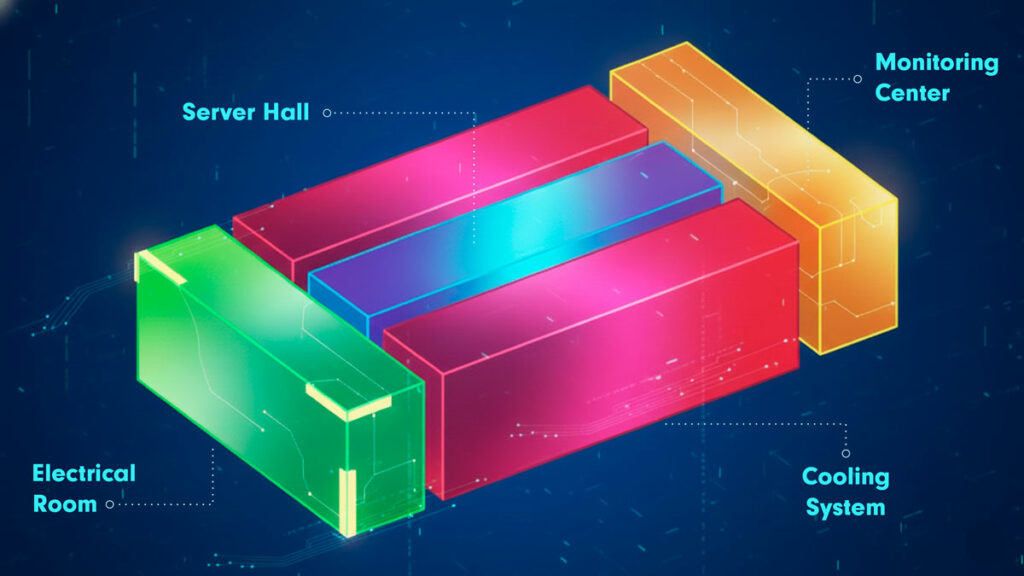

What do data centers include?

A typical data center includes several specialized zones: server halls filled with racks of compute hardware, cooling systems maintaining precise temperature control, electrical rooms with backup power systems, and monitoring centers where operators track performance and uptime.

As our design tools, BIM workflows, and AI models grow, so does the demand for the physical infrastructure behind them.

The scale of this expansion is unprecedented, with new hyperscale centers being built around the world to fuel our increasingly connected workflows.

Global data center construction grew by nearly 30% in 2023 alone, with more than 350 new hyperscale projects underway across the U.S., Europe, and Asia. *1

But if our cloud is expanding faster than our understanding of it, maybe it’s time to ask: do we really need to keep building more data centers? or this is just a buble fueled by the AI Hype?

What are the requirements to build a Datacenter?

Building a data center requires massive and reliable infrastructure: redundant power feeds, UPS systems, generators, extensive cooling and HVAC capacity, a substantial water supply for cooling, and diverse fiber connectivity.

Facilities must also meet strict physical and cybersecurity standards, fire-suppression requirements, and zoning conditions, along with enough land to support current operations and future expansion.

For hyperscale data centers, these needs rise dramatically—often 48,000 MWh of electricity per month, 300,000 m³ of water per month, and at least 100 acres of land.

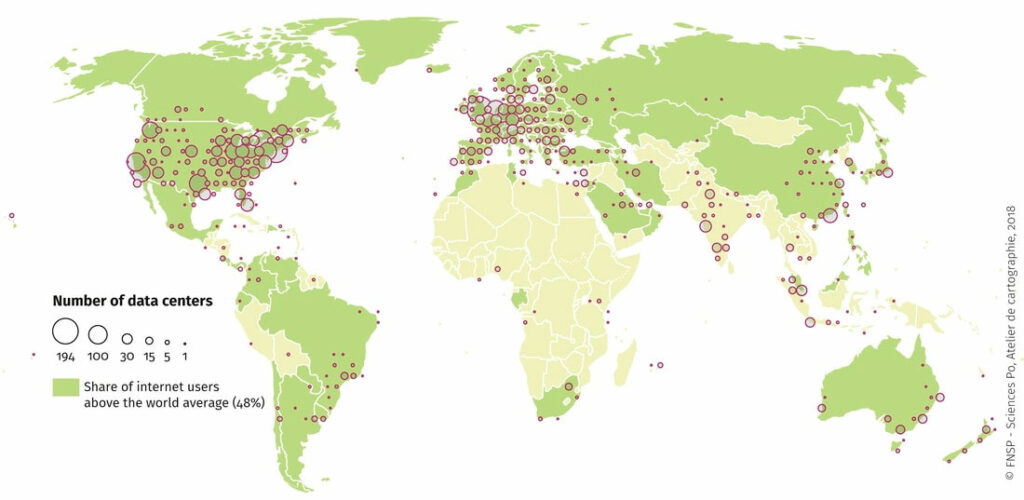

Because of these enormous demands, the global concentration of data centers is highest in the United States and Europe, where stable power grids, abundant fiber networks, favorable climates (in many regions), political stability, strong regulatory frameworks, and access to large tracts of suitable land make deployment feasible at scale.

China follows as a third major hub due to its rapid digitalization, government-driven technology infrastructure expansion, and massive population requiring large volumes of data processing. These regions have the unique combination of energy capacity, connectivity, water availability, land, and economic incentives necessary to support hyperscale deployments.

Would decentralization solve anything?

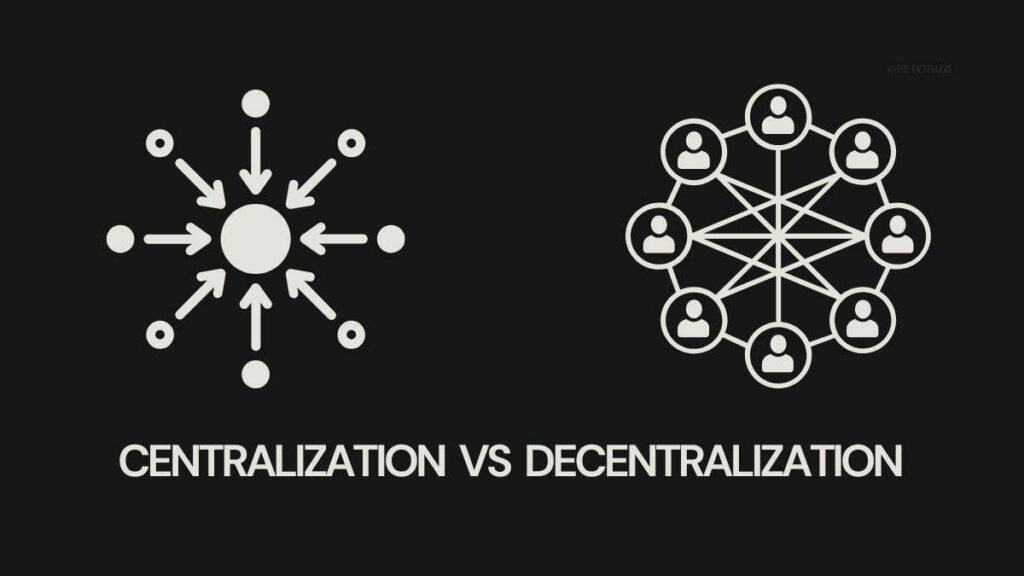

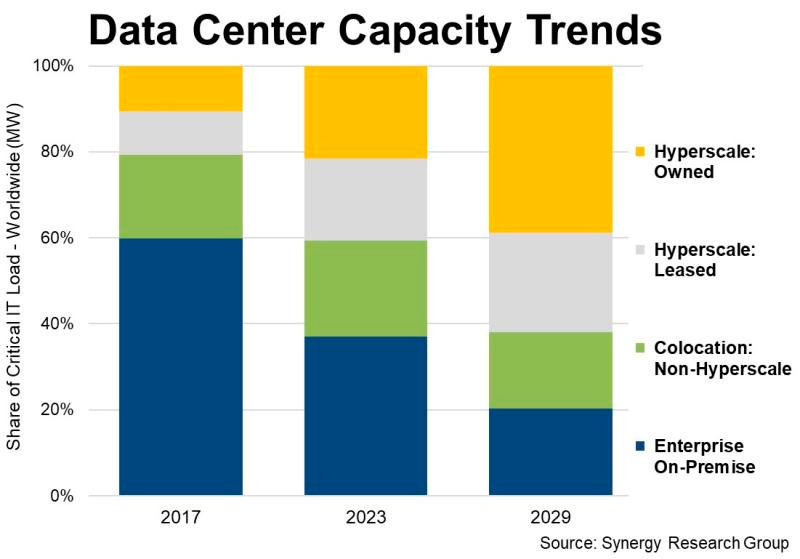

While some argue that edge computing and decentralization might reduce the need for large data centers, the reality is the opposite: they actually increase the total number of facilities.

Edge computing places smaller, localized data centers closer to end users to reduce latency, support real-time applications, and offload traffic from core networks—but these edge nodes supplement rather than replace hyperscale sites.

The large, centralized data centers still handle massive storage, AI training, backups, and global workloads, while edge sites act as fast, distributed extensions of that core.

Instead of shrinking the infrastructure footprint, decentralization creates a layered system: hyperscale centers at the core, regional centers in the middle, and thousands of micro-data centers at the edge.

In other words, edge computing doesn’t eliminate big data centers—it adds more, improving performance and resilience while expanding the overall global data center ecosystem.

Is there anything that can be done from a technical perspective?

From a technical perspective, the most promising way to slow the proliferation of data centers is to make computing itself more efficient—primarily through advances in hardware.

Specialized chips such as domain-specific accelerators, AI processors, and high-efficiency ARM-based architectures already deliver far better performance per watt than traditional CPUs, and emerging technologies like optical interconnects, liquid cooling, and ultra-dense server designs help extract more compute from the same footprint.

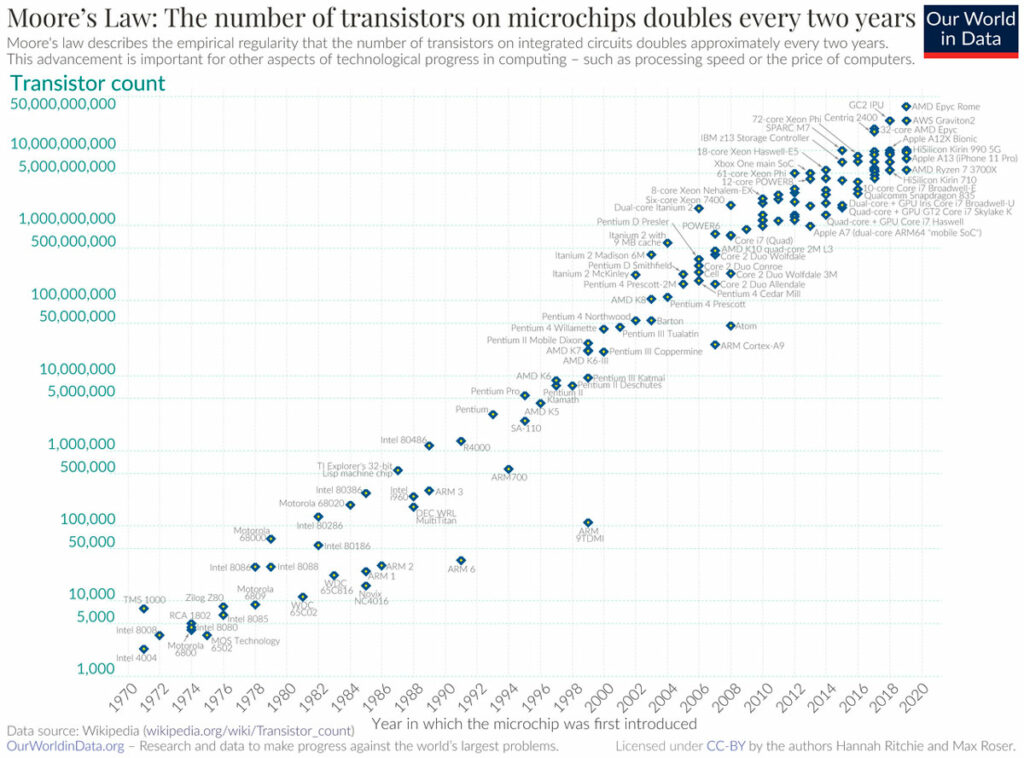

But even with these improvements, the industry faces a fundamental limit: Moore’s Law is slowing down, meaning transistor density and efficiency are no longer doubling at the pace they once did.

As a result, the speed at which chips become more efficient can’t keep up with the explosive growth in demand for AI, cloud services, and digital infrastructure. These efficiency gains may temper the expansion rate, but they won’t reverse it.

What happens if AI becomes more efficient?

Just as we start recognizing the limits of our global infrastructure, we’ve created something that pushes them further: Artificial Intelligence.

The irony is clear—we built a system promising infinite digital capacity, only to feed it an almost limitless appetite.

Training large models is massively energy-intensive; GPT-3 alone used 1,287 MWh, about what 130 U.S. homes consume in a year. Newer techniques like DeepSeek’s claim up to 90% energy savings, showing progress but not yet the norm.

Each AI leap demands more compute, more cooling, and more physical space. AI doesn’t live in “the cloud”—it lives in data centers, and it’s driving their expansion at unprecedented speed.

As for whether tiny, ultra-efficient models could reduce the need for data centers, the short-term answer is no.

Advances in compression, quantization, and specialized hardware help, but they’re outpaced by the size of new models and the explosive growth in global AI use.

Smaller models will improve edge devices, yet they can’t replace the heavy infrastructure needed for training and serving frontier systems.

Today, only 10–20% of data center capacity is tied to AI; the rest powers cloud services, enterprise systems, storage, streaming, and telecom. As AI spreads across every industry, that share will rise—meaning total data center demand will keep climbing, even as AI becomes more efficient.

Do we really can only blame AI?

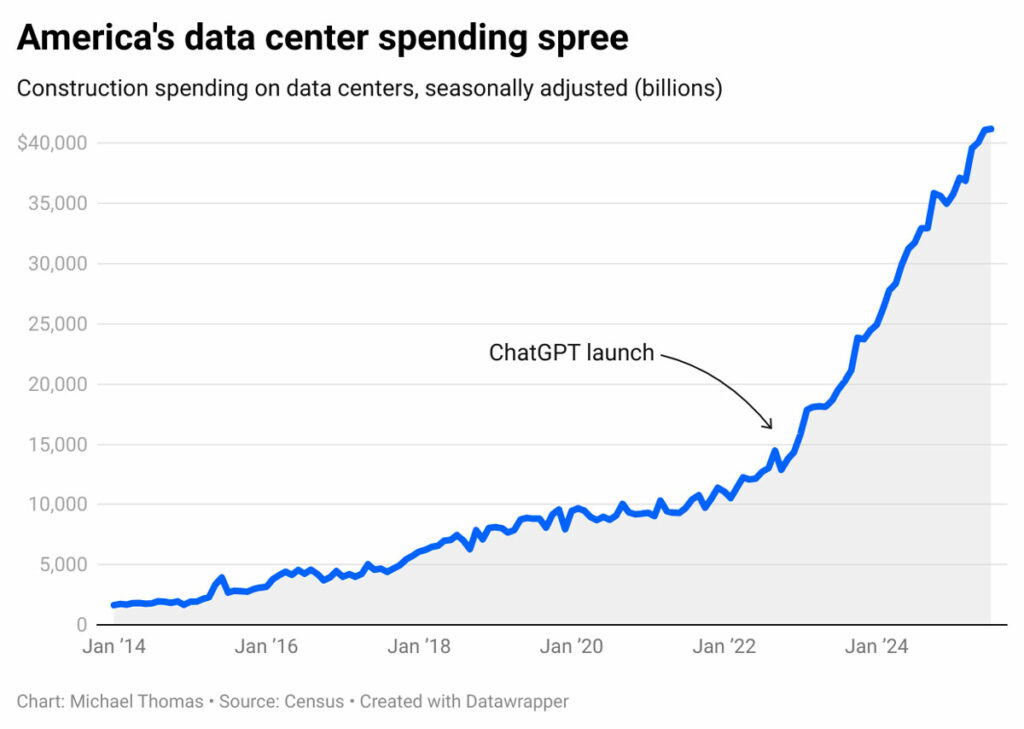

The surge in data center construction over the past few years is often attributed to the rise of artificial intelligence, but the reality is more nuanced.

Hyperscale expansion has been underway for well over a decade, driven by cloud adoption, streaming, enterprise SaaS, mobile computing, and global digitization.

AI has unquestionably accelerated the pace—especially GPU-dense facilities built specifically for training and inference—but it is building on top of a long-standing growth trend rather than creating it from scratch.

The key question is how much of today’s construction boom represents genuine AI-driven demand versus the continuation of an existing trajectory in which cloud providers continually expand capacity to stay ahead of future workloads.

The Capacity Gap

To keep up with rising digital demand, companies have accelerated their build-out of hyperscale data centers.

Today, there are over 1,100 hyperscale facilities worldwide, with the United States hosting more than half of them—a number that continues to grow each year as major providers expand their footprints.

What’s emerging now is a strategic question: how much of this rapid expansion is driven by actual near-term demand, and how much is motivated by competition, market positioning, and the fear of being left without capacity when the next big surge arrives?

Cloud providers are racing to secure land, power, and racks in anticipation of future workloads, but it remains unclear how quickly that capacity will be fully utilized—or whether some of it is being built ahead of real, measurable need.

What’s coming next

Data centers have become the silent architecture beneath every digital workflow—from BIM models and cloud platforms to the AI systems reshaping the AEC industry.

Their rapid global expansion isn’t the product of a single force but the accumulation of decades of digitalization: cloud adoption, mobile computing, streaming, enterprise SaaS, and now AI.

What AI has done is compress that timeline, accelerating demand for high-density compute and pushing providers to build capacity faster than ever.

Even if today’s surge proves to be partially a bubble—driven by competition, land grabs, and the fear of falling behind—the construction of data centers might slow down, but it will never stop.

The underlying demand for storage, connectivity, compute, and global digital services continues to rise every year, regardless of hype cycles.

Whether current build-outs are fully justified or partly anticipatory, one reality remains: the world is not moving toward fewer data centers. I

t is moving toward more, in a layered system of hyperscale, regional, and edge facilities.

The challenge ahead isn’t deciding whether to build them, but ensuring that the infrastructure we create today is flexible, efficient, and ready to support the next decade of digital acceleration.

Deborah Dieguez

I'm a Design Technology specialist who helps turn complex challenges into scalable, cloud-based solutions. My focus is on design automation and interoperability, transforming BIM from a simple tool into a powerful, data-driven workflow. My expertise lies in exploring how technologies like AI and programming (Python, C#, Revit API) can optimize processes and unlock new levels of collaboration in the AECO industry.